- Home

- James Raffan

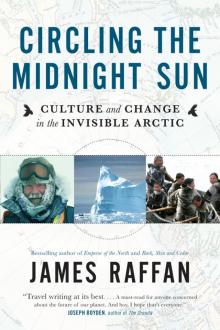

Circling the Midnight Sun

Circling the Midnight Sun Read online

CIRCLING the MIDNIGHT SUN

Culture and Change in the Invisible Arctic

JAMES RAFFAN

Dedication

To Phyllis

CONTENTS

Dedication

Map

Prologue

1. Living the Sagas (Iceland)

2. Voices of the Sacred Mountain (Norway)

3. We Have the Power (Sweden)

4. Things Go Better with Santa (Finland)

5. Hidden Truths (Russia)

6. Semjon’s Obshchina (Russia)

7. A Mask for Luck (Russia)

8. Yamal Reindeer (Russia)

9. Upriver (Russia)

10. Shaman’s Dream (Russia)

11. Road of Bones (Russia)

12. Mandar’s Smithy (Russia)

13. Arctic Gold (Russia)

14. Snow Wind (Russia)

15. Fate Control (Russia)

16. Ninety-Three-Year-Old Sourdough (Alaska)

17. Ho, Ho, Ho (Alaska)

18. Breakfast with Clarence (Alaska)

19. Landscape and Memory (Canada)

20. The Atanigi Expedition (Canada)

21. Bearness (Canada)

22. Walking Backwards into the Future (Canada)

23. Greenland Leading the Way (Greenland)

24. Home Stretch (International Waters)

Epilogue: After the Cold Rush

Acknowledgements

About the Author

Advance praise for CIRCLING the MIDNIGHT SUN

Credits

Copyright

About the Publisher

Map

PROLOGUE

The idea of travelling around the world at the Arctic Circle had its genesis for me in two very different moments. The first was the decision that saw my newly married parents board the transatlantic ocean liner Empress of Scotland at the docks in Liverpool to travel to Montreal, to start their new life in southern Ontario. Since my first adventures by canoe, five decades ago, my parents have always been hungry to hear about the North and to revel vicariously in the life their choice created for their only son. My parents emigrated to Canada instead of South Africa or Australia, choosing north instead of south. And I have been increasingly conscious of this decision as my life as a first-generation Canadian has progressed.

The second moment was much more raw and recent. A group of British and Canadian politicians, bureaucrats, scientists, and academics—scholars all—who meet biannually to discuss an emerging world issue chose “The Arctic and Northern Dimensions of World Issues” as their theme in 2010. I was fortunate to be one of those invited to join them at a two-day meeting in Iqaluit, the capital of the Canadian territory of Nunavut, on Baffin Island. As often happens at gatherings such as this, there were a couple of Inuit presenting, but the delegate list was heavily skewed toward non-indigenous men and women, like me, with addresses in the middle latitudes.

A young British geologist listened carefully to a presentation by an Inuit woman who talked about two goals: preserving the natural world that is and has been since time immemorial the coastal precinct of her people; and supporting industry, particularly emerging oil and gas interests, in creating jobs for northerners. The geologist then asked how the Inuit could expect any sympathy at all if they said they wanted to preserve nature and fight climate change and then go on to hunt polar bears and support the very industry that was producing the fuel that was causing buildup of carbon in the atmosphere. Was this not a bit of a contradiction?

If looks could kill, that young geologist would have been vaporized on the spot. The Inuit woman paused and then quietly hissed, “We don’t need your sympathy. We live here. This is our home. It is more complicated than that.”

When the film An Inconvenient Truth plays in theatres worldwide, when its subject, Al Gore, wins a Nobel Peace Prize and the film wins an Oscar, it is clear that much of the world is looking north because of climate change. And in some ways, like so much of the exploration literature that came before, the reportage on global warming—An Inconvenient Truth as Exhibit A—is much more about physical and so-called natural science than it is about people or cultural science. For this reason, again in significant measure thanks to Gore’s game-changing film, the poster child for global warming has not a human face but that of a polar bear. And, ironically, when it comes to raising money to build public awareness, this is not a bad thing.

But there are people who live in the Arctic, four million of them, in eight countries, speaking dozens of languages and representing almost as many indigenous ethnicities. These are the people who know the North best and, sadly, the people whose voices are least heard and little understood either by those who make decisions or by the rest of us, who are benefitting increasingly from the resources the Arctic has offered and continues to offer at an accelerated pace as the northern ice cap melts.

Life for these northerners, like life for everyone else on the planet, is changing. But global warming is the least of their worries. On whatever social index one might choose—measuring housing, health, education, violence, suicide, infant mortality, water quality, language erosion, or cultural decay—northerners are at the top, or bottom, of the heap. Occupants of the middle latitudes are worrying about climate change and looking north. Northerners are worrying about their very survival and looking south. They don’t need sympathy. They need to be heard.

And that’s how this book came about. Having crossed the Arctic Circle for the first time in 1977, when I stuffed a newly minted bachelor of science honours degree in my sock drawer and headed north to the Mackenzie Delta to build metal buildings for Esso—speaking of contradictions—I have spent part of almost every year since living, travelling, researching, visiting, drinking tea, and wandering somewhere north of sixty.

With the north as a constant reference point since then, I have come to see that while Western civilization appears to be on a crash course with itself, the North has wisdom that could come to bear on solutions to emerging environmental and geopolitical problems. So, having spent a goodly amount of time in the North American Arctic, I thought it might be timely and worthwhile to expand these travels and follow the Arctic Circle around the world, to see what I might see, to continue learning from northerners.

The first thing I learned was that it is much easier to say you’re travelling around the world at the Arctic Circle than it is to actually get to that lofty latitude and move along the line. But that was the goal, and this is its story. It is not a textbook or a scientific tome—nothing of the kind. It is one person’s account of getting a notion and enacting it, with all of the joys, fumbles, and surprises along the way, amply illuminated by the faces of northerners in Iceland, Norway, Sweden, Finland, Russia, Alaska, Canada, and Greenland who welcomed a “neighbour from across the pole” with open arms.

This story takes readers through twenty-four time zones and 360 degrees of longitude. The nominal latitude of the journey was 66°33’ north, plus or minus, depending on who was around and what kind of transportation and infrastructure was available. However, a journey following the Circle exactly, were such a thing possible, would be 17,662 kilometres long. With one detour and another, my peregrinations totalled five or six times that length, door to door.

The story begins and ends at Greenwich Mean Time (where time zones begin) and as close to the prime meridian (0° longitude) as possible—in Iceland. Because it is located on an upwelling of the volcanically active Mid-Atlantic Ridge, Iceland happens to be the only place on the Arctic Circle where new land is being created. More significantly, however, Iceland is the only country among the polar eight that does not have an indigenous population. It is also the home of the oldest written text

s anywhere in the circumpolar world. The story begins and ends in Iceland for all these reasons, and because this country provides a political counterpoint to the variety of projects in the other seven countries to devolve power to the indigenous peoples of the North. So from Iceland we travel east, toward the rising sun, across the Norwegian Sea to Scandinavia, Russia, Alaska, Canada, Greenland, and back to the tiny Arctic isle.

If the truth be told, however, although I’ve written the story sequentially by time zone and longitude, the various parts of the journey didn’t always happen in the order they fall in this story. I had to take advantage of opportunities, seat sales, visa windows, and invitations as they emerged, so the tale as told here was crafted later to fit into a round-the-world arc of twenty-four chapters.

Because this book is about northern people and northern voices, I have presented their language authentically, in sense and in spirit, in ways that might offend some. For example, in Canada, the term “Eskimo”—originally from a North American Indian word, with a somewhat derogatory tone, meaning “eater of raw meat”—has generally been replaced by “Inuit,” meaning “the people” in the Inuktitut language. But in Alaska and Russia particularly, “Eskimo” is still a term in common parlance, and it is used here alongside references to specific ethnicities, such as Inupiaq or Chukchi.

If you are offended, enraged, energized, or inspired by what this book tells you, then you will share some of what I experienced when circling the midnight sun between June 2010 and October 2013. To be sure, there are wrongs to be righted and much work yet to be done.

1: LIVING THE SAGAS

It was not the Arctic you might expect. It was lush and warm and greener than Greenland. There were blue poppies here the size of dinner plates. And the last polar bear to arrive here was shot dead as an undesirable. It was sad, really. There was a time when sea ice would last through the summer months in the Denmark Strait. Bears would use these rafts for loafing between spring and fall. But with global warming, that option was gone. Icelandic scientists reckoned this bear probably swam the last of the 430 kilometres from its winter range on the ice of eastern Greenland. The unsuspecting animal made landfall in the West Fjords region of Hornstrandir, in northwestern Iceland. It shook itself off and wandered up the beach, only to be dispatched as a threat to public safety by the local police chief, who feared that it might make its way to one of the towns on the other side of the broad Húnaflói fjord.

Icelanders have always done things a bit differently. The bear’s role in municipal politics is one example. In the wake of the country’s financial collapse in 2008, the comedian Jon Gnarr decided to run—successfully—for mayor of Iceland’s capital, Reykjavik, a city of some two hundred thousand people. Gnarr and his Best Party promised free towels at public swimming pools and a “drug-free parliament by 2020”; moved by the bear incident, he semi-seriously proposed that instead of shooting hapless polar bears that turn up on Iceland’s shores, authorities should instead put them in the municipal kids’ zoo.

When I arrived in Reykjavik a couple of summers later, no bears had tested the proposed policy, but Gnarr was still mayor. Towels, sadly, in the many amazing geothermally heated public swimming pools in town, cost 350 Icelandic krónur (C$3). Neck deep in one of these human soup pots, cheek by jowl with beefy Icelandic men, I gazed beyond the fence to snow-capped mountain peaks in the distance through a haze of semi-fetid hot steam and lingering volcanic ash. During this geothermal interlude, I reflected on a populace that would elect a polar-bear-loving mayor and, more broadly, on this Arctic nation’s commitment to letting the voice of the people prevail, even if the voice was as offbeat as Jon Gnarr’s.

The tumult that immediately preceded Gnarr’s electoral triumph was all about bad banking, megalomaniacal financing, and Iceland’s struggle to recover after the economic crisis in 2008. The hero, or the pariah, of this financial drama was another Icelandic iconoclast: the president, Ólafur Ragnar Grímsson (elected for a fifth term in 2012).

When asked by the United Kingdom and European countries to cover the debts of three private Icelandic banks that had stiffed thousands of customers out of billions of krónur in savings, in the so-called “Icesave crisis,” the Icelandic parliament—the Althingi—voted to pay for the bailout. However, before that decision could become law, President Grímsson, true to his Icelandic roots as a dyed-in-the-wool democrat, called upon the little-used powers of his largely ceremonial office to hold a referendum. Was this what the people wanted to do with public funds? A solid majority of voters responded with a resounding no. The president relayed this message to British prime minister Gordon Brown and many others in the international financial community. Brown had already put Iceland on the British list of terrorist states and agencies, alongside al Qaeda and the Taliban. Today, however, it is clear that the debts of these particular banks will be almost fully covered by the recovered assets.

Through Icesave, the loss of retirement funds, the collapse of banks, the bankruptcy of hundreds of firms, and 11 percent unemployment, the Icelandic króna dropped to half its value, but the Icelandic people did their best to stick to their principles and weather the financial storm. Some of the finance wizards involved in the economic crisis were later accused, tried, and convicted of all relevant charges, but that process is still not over. Homes of individual Icelanders in greatest need were saved through national mortgage protection, and other measures were instituted to help them pull through. In addition, political and judicial reforms were brought in. Now, the unemployment rate is 4 percent, but 9 percent of the population has fallen below the poverty line.

Although he did not play a direct role in the political rivalry throughout the crisis, President Grímsson was determined to change how business was done. The prime minister fell. There were riots in the streets until the change of government. The international community glowered at the Central Bank of Iceland, to whom no one in the financial sector was talking. Still, Iceland negotiated an agreement for a substantial currency swap with the Central Bank of China. Elsewhere, banks and corporations, notably in the United States, fell into crisis as well, despite the fact that they were propped up with public funds. But a US$2.1-billion loan from the International Monetary Fund and important support from the Nordic countries, Poland, and the Faeroe Islands allowed Iceland to stay its economic course. By 2011 it seemed to have turned toward safe harbour, but with continuing state debts, bank debts, and foreign exchange restrictions, the crisis has lingered for years.

As I read about all this in Canadian papers, Grímsson fascinated and inspired me, not only for his courage and his convictions during the financial crisis but also for his vision in other areas, particularly climate change and its implications for the rest of the world. When an opportunity presented itself for me to join a fellow writer and traveller, Ari Trausti Guðmundsson, in a delegation to visit President Grímsson at Bessastaðir, his official residence in the school-cum-farmhouse near an ancient Icelandic church on the verdant Alftanes Peninsula, I jumped at the chance to meet this modern-day political explorer before heading further north.

Over tea in china cups in the spacious living room looking out across manicured lawns to the mountains beyond, the president was charming and funny. He showed us photos of the Reagan-Gorbachev summit in Reykjavik in 1986, when Vigdís Finnbogadottir was president, and the elaborate clock the Russian had given her as a thank-you gift. (“As far as I know, it never worked,” Grímsson said.) He explained that for most of the time that the American air base was operating at Keflavík using fuel brought in from the U.S., Iceland itself was running on oil imported from Russia. So much for Cold War solitudes behind the scenes in Iceland.

Climate change had been on Iceland’s political agenda since at least 1996, when the country became a founding member of the Arctic Council along with Finland, Norway, Sweden, Russia, the United States, Canada, and Denmark (on behalf of Greenland). Grímsson was straightforward and direct in his pragmatic assessment of what wa

s happening in the world.

“We should be concerned about the Arctic for many reasons. People have lived all over the Arctic for thousands of years. When the Western world started waking up to Arctic issues, the Cold War covered them up. It is only in the last twenty years that we have been looking at things as they are. And now climate change has speeded that up to the point that the Arctic has become the most important part of the planet. First, the U.S. Geological Survey estimates from 2008 suggest that 13 percent of the world’s untapped and undiscovered oil and 30 percent of undiscovered natural gas are in the Arctic. Secondly, climate change is happening three times faster in the Arctic. And thirdly, with the melting of the ice, you might even say unfortunately, there will be new shipping opportunities, which will reduce shipping distances by almost a half and have an impact on world trade, not unlike the effect of the building of the Suez Canal one hundred years ago.”

He painted a picture of Iceland as a hub in this new international trading network, strategically situated at the terminus of both the Northwest Passage and the Northern Sea Route. As the summers have lengthened and the ice has thinned and become less extensive, tens of ships and thousands of tonnes of freight moving through Arctic waters are becoming scores of ships and millions of tonnes. Countries with no Arctic connection are building icebreakers and ice-hardened freighters. China’s icebreaker MV Xuĕ Lóng (Snow Dragon) was well known to Grímsson; with his blessing, it would steam right across the top of the world from Shanghai to Reykjavik in the summer of 2012, confirming Iceland as the Arctic’s central station: a port, a fuelling stop, a transfer point, or a handy stopping place on the way to or from almost every significant port in the world via the North Pole.

“If you talk to the leadership of China,” Grímsson said, waving his finely manicured hand for emphasis, ice-blue eyes burning with sincerity, “when you ask them why they are so interested in Iceland, they would tell you soon in the conversation that when China has become the primary trading partner in the world, they will of course have to look at the northern sea routes between Europe and America and Asia to maximize efficiencies. And that is why I can tell you now that throughout my presidency I have received more delegations in Iceland from China than from the U.S., Britain, Germany, France, Italy, and Spain combined. When the European Union countries were pressuring us to take responsibility for the failed banks, and the United States authorities had simply lost interest in Iceland, the president of China and his prime minister, Wen Jiabao, were the people we were able to have a dialogue with. That’s one of the indications that China is here now, not ten or twenty years from now.”

Circling the Midnight Sun

Circling the Midnight Sun